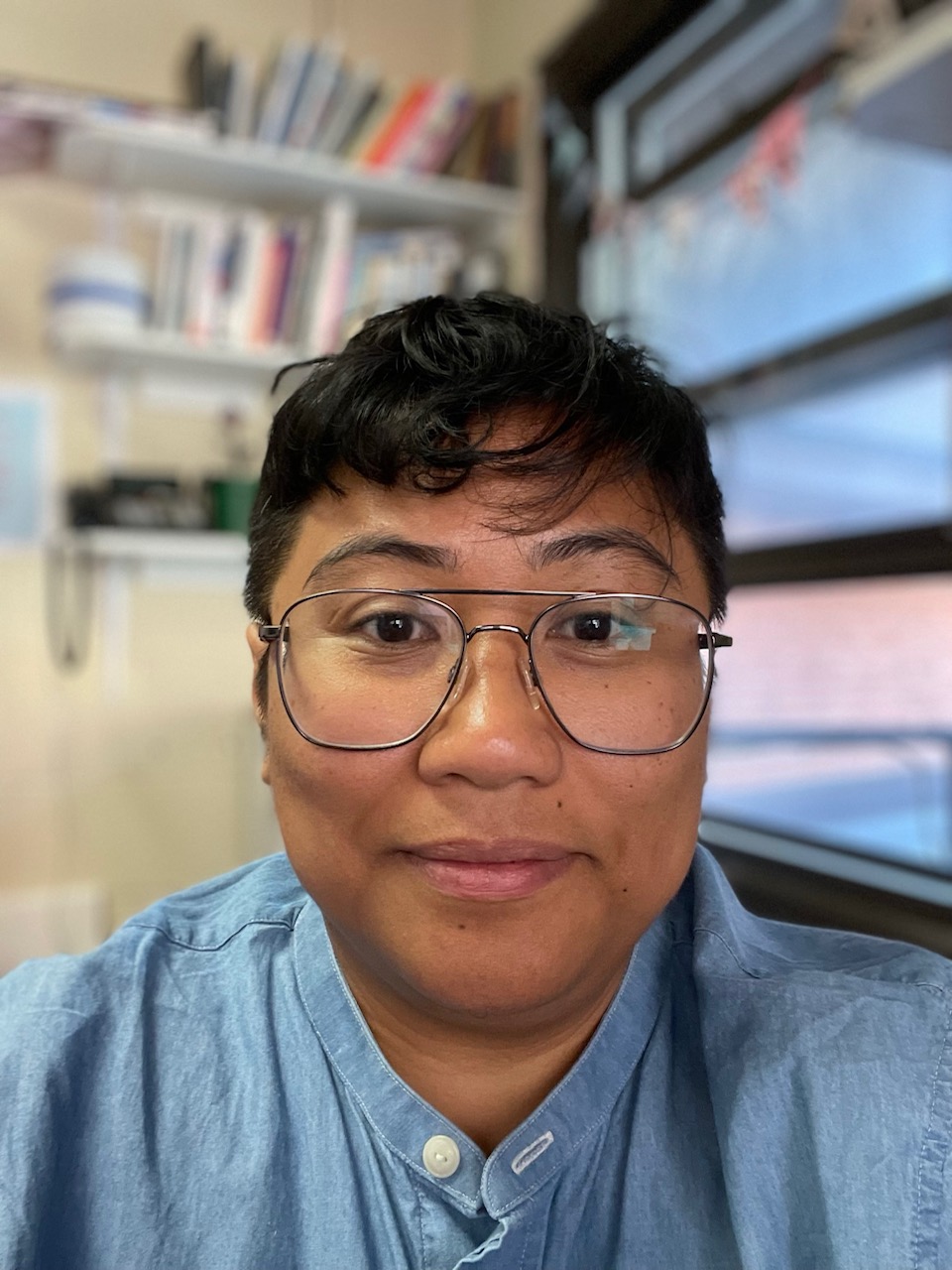

Joshua Levy’s Writing Space

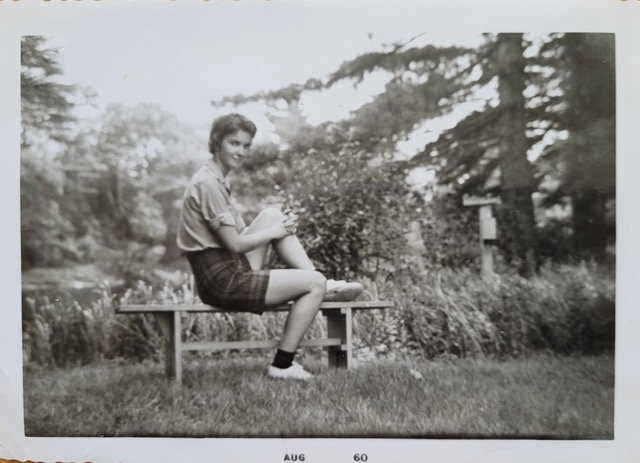

My writing space is full of old things. I have a heavy antique desk rescued from a vintage clothing store in my neighbourhood in exchange for $100 and a bad back. On top of my writing desk sit framed photos that I inherited from my grandmother after she died. The photos used to remind her of me. Now they remind me of her.

Under the desk is a dark green pillow my white cats are determined to turn snow white. The rolling ridged wood acts as a cat forcefield when I’m not at the desk. The writing surface pulls out to create more space.

My chair is also an antique and incredibly uncomfortable, which I like: It’s important that I not become too comfortable when writing.

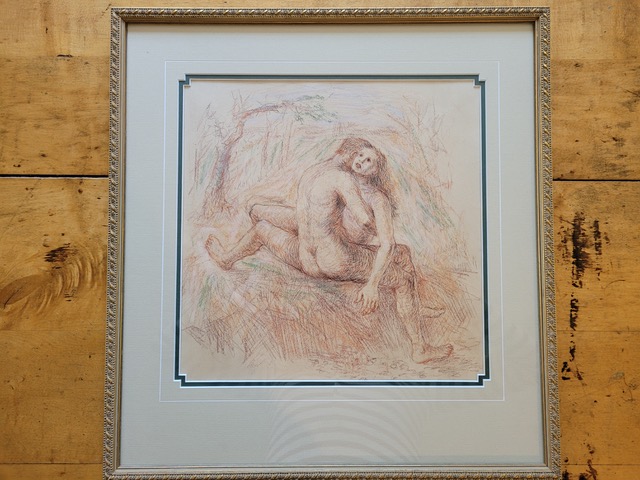

On the wall above is an oil painting that I painted during those brief three months in my twenties when I painted.

I like to place a photo of a hunched-over Leonard Cohen at his typewriter in front of me when I write. Leonard’s scowl says: “Josh, stop looking at me and get back to work blackening your pages.” The photo is signed on the back by his lover at the time, Dominique Issermann, who took the photo.

I usually place a thermos filled with hot tea on the Portuguese tile coaster on the left — I used to place a mug here but there are only so many times I can spill liquid on my laptop.

I write on my Macbook Pro laptop.

The black Greek fisherman’s cap on the right belonged to my friend, Steven Heighton. It goes on my head when I find myself asking: “What would Steve do to make this story better?” Sometimes I just put it on to feel close to him again.

I tend to keep the inside little compartments empty. A big exception is in the top right compartment where I usually stash a guitar pick or two. During breaks, I’ll often grab my acoustic guitar nearby and begin to strum.

When the writing day is done, I push the extension back inside the desk and roll down my wooden ridged cat forcefield.

Joshua Levy has been published by Oxford University Press, Vehicle Press, Mansfield Press, and numerous literary magazines and was CBC’s Writer-In-Residence. He won the CNFC/Carte Blanche Nonfiction Prize and Prairie Fire Nonfiction Prize, among others. www.joshualevy.net

Photos courtesy of Yannick Forest.