Sleeping with the Author

“When it comes to fighting against white supremacy, it’s not just what you stand for, it’s who you sit with.”

–Jamaya Khan, Maclean’s, August 16, 2017

“Now, mind, I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest.”

–Ralph Ellison, Paris Review Spring, 1957

Editing the work of friends and family is a common goodwill gesture, often done as a favour, or, as is the case with certain literary couples, by design. John Gregory Dunne once told the New York Times that he and Joan Didion serve as one another’s “first reader, absolutely.” Glen David Gold described his and Alice Sebold’s harmonious writing-and-editing rhythms as expressions of the couple’s “complementary neuroses.”

My spouse and I are three decades into editing one another’s work, a lively partnership we safeguard by confining ourselves to separate sandboxes—his, in academia; mine, in arts and culture. The rise of Trump disrupted this peaceable arrangement. Suddenly, my husband was exploring explosive family history in a personal essay I’d encouraged him to write.

What I discovered in the process was unsettling. As an editor, I want the truth exposed. As a spouse, I sometimes dread it.

The following exchange with Ron Grimes took place in August and September, 2017, while he was submitting “The Backsides of White Souls” to literary magazines in the U.S. and Canada.

Note: The piece went on to be rejected by seven American publishers and accepted by one British online publisher. Two Canadian publishers said “yes” to Grimes, one of which was CNQ, which posted the essay online in February, 2018. You can read the CNQ essay here.

—Susan Scott, TNQ nonfiction editor

Susan Scott: Canadian editor, American scholar. I wonder, have I done justice when it comes to your incendiary essay?

Ron Grimes: Sure you have. You’re doubting?

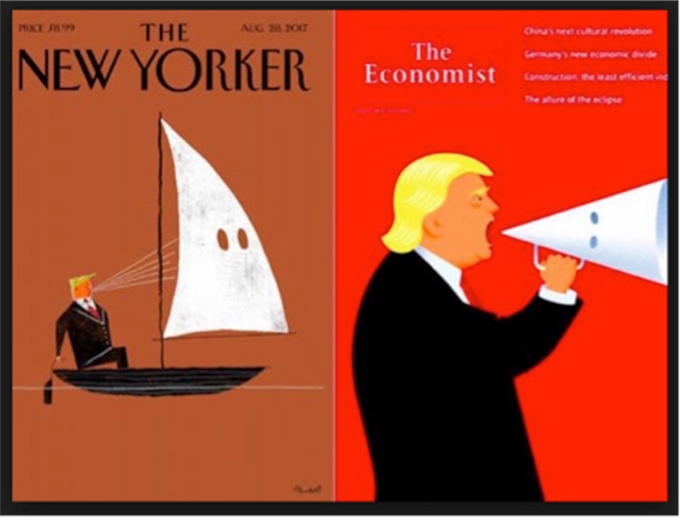

SS: The aftermath of Charlottesville, Virginia, got me thinking about the marriage of editing and culture. Megan Garber wrote in The Atlantic about Trump’s addiction to flouting norms—even when he’s handed a statement that’s been vetted, he will not stay on script.

His behaviour reinforces this dismissal of the rational, cooling space that editing affords. Left and right, we’re seeing that cultural cooling space collapsing.

But cooling off can also mean constraint. Editing can just as easily undercut what the cultural moment calls for. “The Backsides of White Souls” exposes racism in an old American family. Looking back, I wonder, have I simply reined you in?

RG: Sometimes, but I knew you would do that, and I invited it. This essay is personal and dangerous. I kept losing perspective on it and needed your editorial eye. We both know the value of trying to imagine “the reader’s” eyes. We both believe that blindly accepting an editor’s suggestions is a mindless exercise. But we’ve done this before. The ultimate decision is the author’s, so I had to figure out when to let you rein me in and when not to.

SS: Fair enough. I wanted to think with you as you wrote, and I wanted you to think with me—not just resist, or capitulate to my suggestions. Not that you’d ever capitulate, really, but the creative tension between us colours how you write, and how I edit.

So, what about the spousal edit? When is it effective?

RG: Well, for instance, you helped me rethink the knife on the bedpost. I had that image in early drafts, and you wanted me to take it out.

SS: Right, the early draft you sent to friends confessed…

RG: Sorry, it wasn’t confession, it was fact. That knife had hung on the bedpost since my teens. You never complained about it until you read the essay, when you said…

SS: I said, “Okay, even if the knife does hang there, is that how you want to introduce yourself to readers? Unless you want to shock them, think about cutting the reference to the knife.” You still had ghosts and guns. Page one, no less. The knife’s important to the story; how it was handled was the question.

RG: Right, I don’t mind if people dismiss me in the last paragraph, I just don’t want them to dismiss me in the first paragraph.

SS: So, was it a loss, excising the knife?

RG: No, I didn’t excise it. The literary knife is back in now—reframed. I put the actual knife away one day when you were gone (and pulled it back out momentarily to stage this photo). I thought, “I don’t need this ritual object hanging here anymore.” Did you notice?

SS: Ah, so that’s what happened. Editorial prompt as ritual prompt; that’s novel. Anything else come to mind?

RG: You and I both love economy and compression in writing, so I asked you to steal some of my words. I also love hyperbole, sparkle, and spew, so I sometimes dump economy. You suggested cutting:

Having moved north of the border to Canada in 1974, one might wish the load of baggage had been left behind, stuffed in a carpet bag and stashed in some remote, deep-south alley. But, as kids used to say in New Mexico, you can’t pee in only one corner of a swimming pool. Canadians put it more discreetly: When America sneezes, Canada catches cold.

SS: Yep, that had to go. Shall we talk about why, or is it obvious?

RG: I still like the passage, but I followed your suggestion. The context was too serious for horseplay. Those lines are now composting in my fragments file, waiting to jump into the next essay.

SS: Right, you know that I’m uneasy, still, about “The Backsides of White Souls” going public.

RG: Sorry to hear that. You urged me to write the essay. Why dread it now?

SS: I asked what you wanted to accomplish, and you said you wanted to make a racket, dragging skeletons out of the closet.

RG: I want white people to talk about being white. So, yes, open the closets and let the skeletons out, let them rattle their bones.

SS: Absolutely, but then what? Scott Gilmore called out Canadian racism in Maclean’s after the violence in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2015, and that was well before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report. As a country, we’re just now admitting we have skeletons, let alone rattling them. Editing your essay made me realize I need to own up to that reluctance.

RG: Meaning what?

SS: You were starting brush fires using religion and politics as kindling. My response was to tamp down the flames. I argued that the longer the thematic checklist, the greater the danger that your characters would be flattened to little more than props. And on the one hand, that’s true. The more themes piled on, the more the clutter, and the less oxygen for power and precision.

On the other hand, your instinct as a writer is to fan the flames. I edited in favour of a smoulder.

RG: Compared with what’s happening in Charlottesville, I’ve built a tiny Boy Scout campfire surrounded by rocks to keep it from spreading. “The Backsides of White Souls” is a complex essay, but I had a hard time figuring out what the argument was. In academic writing I’d start with the thesis and argument. But in this essay I had characters, dialogue and a plot. My problem was less with characters than with plot and setting. They were too elaborate You had to keep straightening out my chronology. Anyway, we agree that an essay needs both a story and an argument, and there’s only so much you can do in 5,000 words.

SS: True enough, but I suggested that you try creative nonfiction (CNF) because it would expose you to techniques for exploring disturbing insights. Of course, like any art form, CNF is demanding. “The essay must be artistically rendered,” as Phillip Lopate says.

Sure enough, there you were, struggling with the form.

Let’s just say, I’m culpable on two fronts. I suggested CNF as a kind of discipline, then pulled back once I saw exactly where it took you.

RG: I asked you to give me homework, and I’ve done it. Sure, “Backsides” needs to be artistically rendered, but it also needs to be ethical and critical. The essay takes up unfinished family, ethnic, and national business that implicates living members of my family. I can’t think only about characters. I also have to think about people. Across five generations mine has been a “good” family, respected in the community. Among us siblings one is an atheist, one “believes pretty much what he believed as a kid,” one is far to the religious and political right, and I am, what shall I say, ludically religious. All these categories are inaccurate, but they will do for now. Two of us voted for Trump, two didn’t. If you asked my siblings, probably we’d say we’re not racist; some of us have non-white friends. In the 1970s we had a shouting match, not typical in our family, followed by an agreement never to talk again about race, religion, or politics. We may love each other, but in the current political climate we’re dysfunctional. America is failing, and the family so far is unable to deal the rifts. We haven’t faced our heritage, so we are unable to negotiate America’s loss of moral credibility.

SS: I see that. I also see ethical tripwires in your writing: whether to use people’s names; how fair it is to expose the voting choices and religious beliefs of family members; how to depict polarizing figures like your grandma. Then there’s the question, do you want your readers to empathize with all these figures?

RG: I do fieldwork on ritual, so empathizing is a part of my academic research. I have to consider the ethics of privacy as a part of my profession. I’ve rewritten the voices and depictions of my brothers and sister dozens of times. I care about their feelings, but I also want to tell the truth—as I see it, of course.

SS: I like that you’ve explored the use of dialogue. Now we hear real voices.

RG: Well, my reconstruction of real voices. My sister’s voice was the most difficult to represent, since our conversations kept breaking down. Trump supporters and Christian fundamentalists will likely read her character as courageous, standing up for her beliefs. Liberal readers will read her religious and political views differently.

SS: Either way, what readers want, I think, are compelling characters who make us think and feel. I want to understand your family, and I want your essay to help me do that. Is that an undue burden for the author? Maybe it is.

Are you showing the essay to your siblings?

RG: Maybe it’s a fair expectation of novels or great short story writers, but for me it’s an undue burden. This is a brief essay, and I’ve presented selected bits—characters, not actual personalities—and that’s as true of me as narrator as it is of the other characters. Even though I don’t use my siblings’ names, I decided against springing the published essay on them, so I am showing it to them before publication. I’ll listen to them, but I may not always take their advice. The essay reveals a big family secret. Some relatives may not like that I’ve told it publicly, but the current political crisis in the U.S. makes hiding irresponsible. Anyway, I first sent the essay to readers whose opinions I respect, people who could help me improve it.

SS: That surprised me, your circulating such an early draft.

RG: That’s part of my writing process, to send an essay out early to colleagues, while I’m still open to criticism and suggestions. Later, I’ll dig in, becoming more resistant to changes.

SS: Another classic difference between us: we have a radically different sense of timing. I suggest that authors hone their work before they show it, on the assumption that, the greater their confidence in the piece, the greater their resilience, weathering critique.

But it’s your essay and your process. And, let’s be frank: no matter how well the work is crafted, it isn’t going to heal the family.

RG: You’re guessing. Sure, it could be a bombshell, but it could also lead to some good, difficult conversations. I read Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir and Writing the Memoir by Judith Barrington. Both tell about writing controversial family stories and getting surprisingly receptive reads by relatives. It’s a risk I’ve decided to take. Are you worried?

SS: I am. We seldom see your family. It’s hard enough, resolving minor conflicts at a distance, let alone your airing family secrets. You also take a stand on how the family functions. People will feel hurt. How that’s going to help, I wonder.

RG: People “may” feel hurt. You’re now playing therapist rather than editor, right?

SS: What can I say? It’s a hazard, sleeping with the author. We both want good, hard conversations about equity and justice, but we both know that those are often easier to have with strangers. Part of what I love about the small magazine world is that we’re exercising whatever modest power we have to open doors for writers. Releasing work that’s vital and authentic is what attracts me to publishing. Editing, for me, is deeply moral work. So here’s the irony: editing your essay made me aware of fears and inhibitions I wasn’t owning up to.

RG: Okay, I have a question for you. Is this the hardest editing you’ve ever done?

SS: In one way, yes. Academic-creative crossover pieces are hard to edit. Knotty. Resistant. But the truth is, it’s been a hard project because I am invested. We’re a small cross-border family that’s ill-equipped to deal with a lot of fallout.

Unintended consequences—I stew about those, too.

RG: Between us?

SS: No, we’re fine. We have a long history of bumper-car editing. You value hyperbole, I value understatement. We clash a lot.

RG: I’m from New Mexico, you’re from Ontario. Bang, bump!

SS: (laughs) Yes. You’re expansive, vocal. Your last book was over 400 pages. I’m a minimalist who works towards peaceful resolution.

Alice Quinn of the Poetry Society of America has spoken to the New York Times about the sense of urgency she’s seeing, what she calls the “reckoning and responsibility” that’s supplanting the introspective, personal tone of yesteryear’s poetry. We’re seeing the same shift in creative nonfiction. As an editor, I’m a fierce advocate for transgressive stories, but inhabiting “The Backsides of White Souls” with you has made me see that I’m also caught between private and public.

Now’s the time for reckoning on several fronts.

That’s where I’m at. And you?

RG: For sure, it’s a time of reckoning. As a Canadian, I too long for peaceful resolution, but as an American I’m not sure that’s always possible. Anyway, I’m still nosing around in literary journals where I hope to publish. I found “The Old Grey Mare,” an exquisite personal essay in the Yale Review by Colin Dayan, who also wrote The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons. We write about some of the same things—ritual, racism, mothers, the South. Reading her essay, then the book, made me realize how similar and yet how different the South is from the Southwest. I sent her an appreciative note. Now we are trading essays.

SS: Say more.

RG: When I read her essay, I thought, wow, that is literary. I wish I could write like that. I vented to you in frustration, “Please, make me sound more like me.” And you retorted that you were trying to get rid of my academic formalisms, make me sound more literary.

SS: Right, storyteller and scholar—you veer between the two.

RG: I don’t care much whether I sound either academic or literary. I would like my writing voice to “sound” like me.

SS: Fair enough. I love your cowboy storytelling voice, but there’s a time and place for it. “The Backsides of White Souls” isn’t it.

Umpteen drafts later, did you find the right voice for the essay?

RG: I’d be the last to know. I’m sure the editors and readers will let me know.

SS: Submitting to this world is new for you. After doing your research, you ended up with fifty-plus pages of notes on literary magazines in the States and Canada. Now you know more than I do. I’m curious, what’s the take-away?

RG: Having taken a grand tour on both sides of the border, I’d say that while magazines might be muses, they’re also Scylla and Charybdis—a rock shoal and whirlpool separated by a narrow pass through which your rowboat essay must pass. Several times I saw submissions rates in the thousands and acceptance rates of two percent. The literary rite of passage is just as daunting as the academic one. I’ve submitted to seven literary magazines and to the radio show, This American Life. I have ten more magazines lined up for September. I expect success, but many failures first.

SS: Okay, but you’re still reading, too. What’s the draw? Why burrow into lit mags?

RG: Same as you, I care about writing. I want to write better. I just read Terence Byrnes…

SS: Montreal writer-photographer, featured in TNQ 106 (Spring 2008).

RG: “South of Buck Creek” in Geist is a fabulous photo essay, so I wrote him. I’m busy trading stories and essays with him too. I rarely communicate with authors, but I am thoroughly enjoying it. But you ask why. This essay could die on the vine, or, if published, the shit could hit the fan. Either way, I want company. I love being a student. I’m hungry to learn from writers who struggle with the same issues. I want to learn how to honour but also to question the ancestors—well, my ancestors. By dragging the skeletons out of the closet, then talking publicly, I want to learn how live more justly—on stolen land, and benefitting from slave labour.

SS: On that we are united. So, you’re not about to quit my sandbox, are you?

RG: Why quit? I’m just getting started.

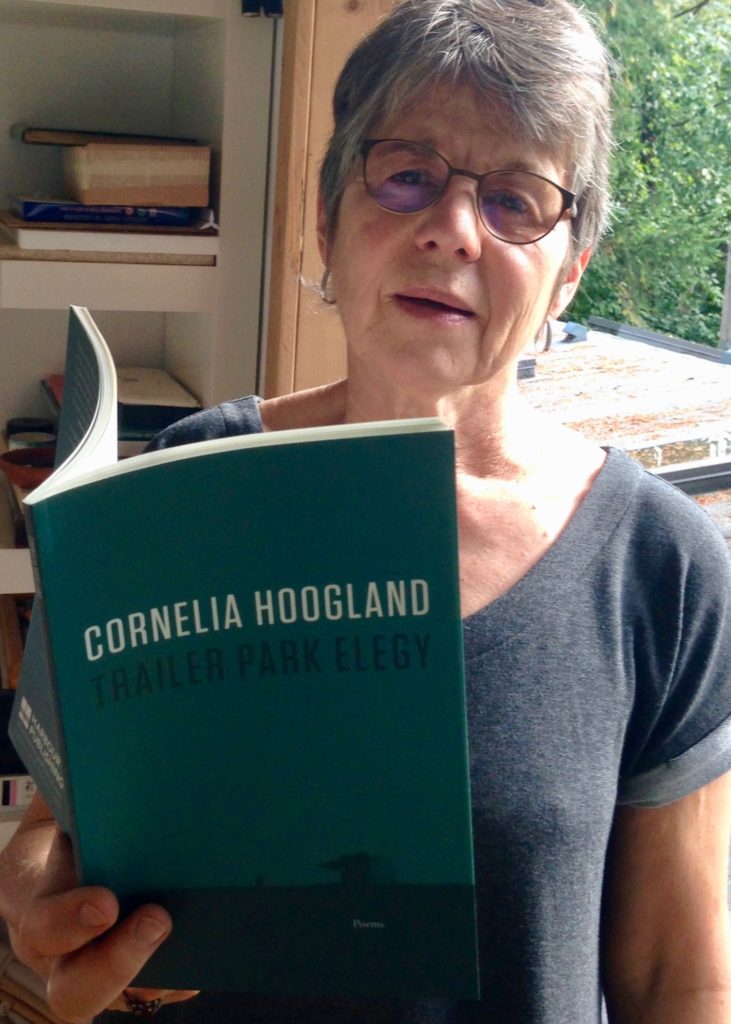

Ron Grimes is co-editor of the Oxford Ritual Studies Series and the author of several books, including Deeply into the Bone: Reinventing Rites of Passage. Susan Scott is TNQ’s lead nonfiction editor and the editor of Body & Soul: Creative Nonfiction for Skeptics and Seekers.

read more